Everything posted by Jade Bahr

-

Watching right now

Because season 3 is about to come I re watched ... and hands down Queen B is one of the best period dramas eeeeeeeeeeever. So goddamn well written and well acted, beautiful and heartbreaking from tip to toe. I'm usually not a big cryer in front of my TV but I found myself weeping a couple of times here 💔😭

-

Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

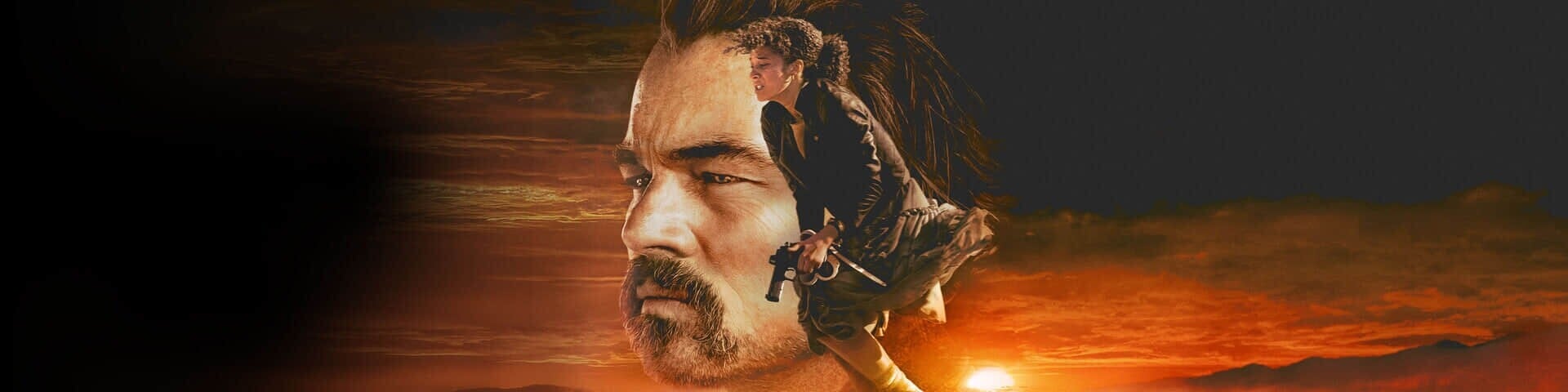

The 25 Best Movies of 2023 The best movies of 2023 took us into the unknown. 15. “Killers of the Flower Moon” (dir. Martin Scorsese) Martin Scorsese may like to think of “Killers of the Flower Moon” as the Western that he always wanted to make, but this frequently spectacular American epic about the genocidal conspiracy that was visited upon the Osage Nation during the 1920s is more potent and self-possessed when it sticks a finger in one of the other genres that bubble up to the surface over the course of its three-and-a-half-hour runtime. The first and most obvious of those is a gangster drama in the grand tradition of the director’s previous work; just when it seemed like “The Irishman” might’ve been Scorsese’s final word on his signature genre, they’ve pulled him back in for another movie full of brutal killings, bitter voiceovers, and biting conclusions about the corruptive spirit of American capitalism. But if the “Reign of Terror” sometimes proves to be an uncomfortably vast backdrop for Scorsese’s more intimate brand of crime saga, “Killers of the Flower Moon” excels as a compellingly multi-faceted character study about the men behind the massacre. Over time, it becomes the most interesting of the many different movies that comprise it: A twisted love story about the marriage between an Osage woman (the indomitable Lily Gladstone) and the white man who — unbeknownst to her — helped murder her entire family so that he could inherit the headrights for their oil fortune (Leonardo DiCaprio, giving the best performance of his career as the dumbest and most vile character he’s ever played). Finding the right balance in this story is a challenge for a filmmaker as gifted and operatic as Scorsese, whose ability to tell any story rubs up against his ultimate admission that this might not be his story to tell. And so, for better or worse, Scorsese turns “Killers of the Flower Moon” into the kind of story that he can still tell better than anyone else: A story about greed, corruption, and the mottled soul of a country that was born from the belief that it belonged to anyone callous enough to take it. full list: https://www.indiewire.com/gallery/best-movies-2023/brody-killers-of-the-flower-moon-copy/ Robert Eggers’ 10 Best Films of 2023 I always look forward to IndieWire’s annual polling where directors choose their best films of the year. This year, 37 filmmakers participated, and they include the likes of Sean Baker, Kitty Green, Ira Sachs, David Lowery, Andrew Haigh, Paul Schrader and Daniel Scheinert. “Killers of the Flower Moon” (Martin Scorsese) — A Scorsese epic at the height of his powers. The scale, richness, and depth of the world were truly inspiring and exceeded high expectations. The cast and casting were immaculate. Lily Gladstone and Ty Mitchell were particular standouts. The story is unflinching and shocking. more: https://www.worldofreel.com/blog/2023/12/31/cf9kci9ztsogx42gpd0nv089gts23o

-

Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

-

The "What Are You Thinking About Right Now?" PIP

- Last movie you saw...

- Phoebe Dynevor

- Hunter Schafer

- Emilia Clarke

- General Celebrity Gossip

- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

In germany (hamburg) KOTFM is #4 of the most visited films in 2023 - before Guardians of the fuckin galaxy just saying. We germans loved and more important watched it- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

- Brad Pitt

- Last movie you saw...

Kinda liked it. And not. lol- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

If Leo ever decides to work with Schrader we already know who he won't be playing LOL- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

The 2023 Georgia Film Critics Association (GAFCA) Nominations The winners will be announced January 5th, 2024. Best Picture “American Fiction” “Barbie” “Godzilla Minus One” “The Holdovers” “Killers of the Flower Moon” “May December” “Oppenheimer” “Past Lives” “Poor Things” “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” Best Director “American Fiction” – Cord Jefferson “Barbie” – Greta Gerwig “Killers of the Flower Moon” – Martin Scorsese “Oppenheimer” – Christopher Nolan “Past Lives” – Celine Song Best Actress Lily Gladstone (“Killers of the Flower Moon”) Sandra Hüller (“Anatomy of a Fall”) Greta Lee (“Past Lives”) Carey Mulligan (“Maestro”) Emma Stone (“Poor Things”) Best Adapted Screenplay “American Fiction” – Cord Jefferson “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.” – Kelly Fremon Craig “Killers of the Flower Moon” – Eric Roth, Martin Scorsese “Oppenheimer” – Christopher Nolan “Poor Things” – Tony McNamara Best Cinematography “All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt” – Jomo Fray “Killers of the Flower Moon” – Rodrigo Prieto “Maestro” – Matthew Libatique “Oppenheimer” – Hoyte Van Hoytema “Poor Things” – Robbie Ryan Best Production Design “Asteroid City” – Adam Stockhausen, Kris Moran “Barbie” – Sarah Greenwood, Katie Spencer “The Creator” – James Clyne, Chris DiPaola, Matt Sims, Lek Chaiyan Chunsuttiwat “Killers of the Flower Moon” – Jack Fisk, Adam Willis “Oppenheimer” – Ruth De Jong, Claire Kaufman “Poor Things” – James Price, Shona Heath, Szusza Mihalek Best Original Score “Killers of the Flower Moon” – Robbie Robertson “Oppenheimer” – Ludwig Göransson “Poor Things” – Jerskin Fendrix “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” – Daniel Pemberton “The Zone of Interest” – Mica Levi Best Ensemble “American Fiction” “Asteroid City” “Barbie” “The Color Purple” “The Holdovers” “Killers of the Flower Moon” “Oppenheimer” https://nextbestpicture.com/the-2023-georgia-film-critics-association-gafca-nominations/- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

U.K. Film Critics Association (UKFCA) Nominations: ‘Oppenheimer’ Leads with 6 Winners will be announced on December 31. Here are the nominees. Best Film Barbie Killers of the Flower Moon Oppenheimer Past Lives Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse Best Director Celine Song – Past Lives Christopher Nolan – Oppenheimer Emerald Fennell – Saltburn Jonathan Glazar – The Zone of Interest Martin Scorsese – Killers of the Flower Moon Best Actress Lily Gladstone – Killers of the Flower Moon Emma Stone – Poor Things Greta Lee – Past Lives Sandra Hüller – Anatomy Of A Fall Margot Robbie – Barbie Best Screenplay Anatomy Of A Fall Barbie Killers of the Flower Moon Oppenheimer Past Lives https://awardswatch.com/u-k-film-critics-association-ukfca-nominations-oppenheimer-leads-with-6/- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

They talked Leo around 43:00 So I watched MAESTRO.... and I'm torned. I kinda liked it... and not. I think the performances are great. Still lots and lots of talking and even more smoking and miserable people 🤪 I don't understand the title of the movie because Bernsteins work is the last thing this movie cared about. It was all about his troubled marriage and his cheating. Wished Matt Bomer had a bigger role actually. The chemistry between him and Cooper is mesmerizing Same for him and Carey Mulligan 🤍 The older make up is oscar worthy though. I also kinda agree with this. Nor he, his performance or the movie deserved such backlash. Why Does Everyone Hate Bradley Cooper’s ‘Maestro’ All of a Sudden?- Jessica Chastain

- Billie Eilish

- Jude Law

- Last movie you saw...

Loved it. Can't wait for part 2.- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

The Wolf of Wall Street’s “I’m Not Leaving” Scene Is Just as Powerful a Decade On Martin Scorsese’s exploration of corporate greed celebrates 10 years on December 25. DiCaprio’s performance – and the film’s warning – has proven ever more prescient. There’s a scene about halfway through Killers Of The Flower Moon, Martin Scorsese’s 2023 epic about the murders of members of the Osage Nation, when Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio have a heated debate about the best way to shoot a man in the head. De Niro’s character, genocidal landowner William Hale is adamant that, when you’re trying to make a hit look like suicide, the front of the head is the way to go. “You told him to do it in the front of the head? Then why he do it in the back of the head?” De Niro demands. “It’s too simple; the front is the front and the back is the back!” “I told him the front of the head, just like you told me. I promise you. I swear on my children!” DiCaprio’s character, the gurning, slow-witted killer Ernest Burkhart stammers. For a film of such leaden subject matter, the scene is surprisingly – and intentionally – funny, with DiCaprio building on his broader comic sensibilities most recently on display in 2021’s Don’t Look Up. Both performances are effective, but DiCaprio’s humour is arguably even more acute when it takes a more insidious form. Instead of a bumbling bumpkin, DiCaprio’s powers shine best when the humour is paired with intelligence and even a malicious, self-satisfied air. We’ve seen it in Django Unchained but, a decade after it’s release, his role as Jordan Belfort in 2013’s The Wolf Of Wall Street (also Scorsese) is yet to be bettered. From his endless extra-marital screwing around to throwing “fun tokens” at FBI guys in cheap suits, DiCaprio electrifies as perhaps the most compelling character in his oeuvre. Nowhere is the essence of Belfort’s self-deception, his epic corporate greed and yes, DiCaprio’s skill, so readily displayed as in the much-memed “I’m not fucking leaving!” speech, delivered at the 02:15:40 mark. In just over two minutes, Belfort’s rallying speech to his troops offers up the most concentrated shot of the quiet menace that laces Scorsese’s most prophetic film. “For years I’ve been telling you guys never to take no for an answer, right?” a contrite Belfort begins, addressing his most loyal stockbrokers, all of whom are gathered as if in mourning for a monarch. “To keep pushing and never hang up the phone… this deal that I’m about to sign, barring me from Stratton, barring me from my home… it’s me taking no for an answer. It’s them selling me and not the other way around. It’s me being a hypocrite.” We can see Belfort’s regret here – not at his actions, but that he has been caught out. Were his hands not tied, had real justice been allowed to triumph, Belfort would continue righteously ripping people off because that is what he deserves to do. Then things really ramp up. “You know what? I’m not leaving,” Belfort whispers to the crestfallen crowd. “I’m not fucking leaving!” he screams to rapturous applause, hugging, and general joyous disbelief among his adherents. “The show goes on! This is my home. They’re gonna need a fuckin’ wreckin’ ball to take me out of here,” Belfort announces as female employees grasp each other, and mouth “I love you!” at him. Like many scenes in The Wolf Of Wall Street, it’s utterly grotesque. What the memes miss is that we aren’t meant to be rooting for Belfort (even if he does look like Leonardo DiCaprio). We’re meant to be horrified by his hubris, and by the cult-like devotion of his followers, each as morally bankrupt as him. DiCaprio, red-faced, struts, screams and peacocks across the front of the room. “They’re going to need to send in the National Guard, or fuckin’ Swat team ‘cause i ain’t goin’ nowhere! Fuck them!” In his violent refusal to step down, despite the full weight of the law commanding him to do so, we see an eerie foreshadowing of another red-faced Wall Street guy refusing to leave office, this time on the 6th of January 2021. As well as being a riotously entertaining time at the cinema, The Wolf Of Wall Street served up a stark warning about greed, populism and entitlement. Scorsese recently recounted that some critics missed the point of the film, prompting another critic to ask “Do you really need Martin Scorsese to tell you that that’s wrong?”. It turns out, maybe some of us did. A decade on, the “I’m not fucking leaving!” scene remains not just a masterclass in minacious comedic performance, and a DiCaprio highlight reel staple, but a warning against unhinged, charismatic leaders. We need to pay more attention than ever, because try as we might, just like Jordan Belfort, they’re not going anywhere, either.- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ Turns 10 Martin Scorsese’s “The Wolf of Wall Street” was released 10 years ago yesterday. Its resonance still looms large. This year, we had two separate Scorsese polls — for critics and readers — and “The Wolf of Wall Street” kept cementing its legacy as the filmmaker’s best film of the 21st Century. According to these polls, it’s either ‘Wolf’ or “The Departed” as the best film Scorsese’s released since 1999. A 10-year-anniversary write-up from Esquire makes claim of ‘Wolf of Wall Street’ being such a prescient film that it ended up predicting the Trump era. I don’t necessarily think it just predicted Trump as much as just this massive cultural change of excess and outrage, which would happen just a few years later. Yes, “The Wolf of Wall Street” opened 10 years ago this week. Directed by Scorsese, the $100 million film grossed $407 million and became the director’s highest grossing film. Critics were split on it, but time has been very kind to ‘Wolf’. I can remember its opening week, the film receiving a dreaded C on CinemaScore, and some journalists being outright pissed at Scorsese’s statement about ego. The main complaints had to do with ‘Wolf’ being materialistic, encouraging greedy behavior, extreme wealth, and advocating for the criminal individuals portrayed in the film. Variety journalist Whitney Friedlander called the film "three hours of cash, drugs, hookers, repeat" and argued that the film was a "celebration of this lifestyle.” I don’t think she got it. In a September interview with GQ, Scorsese revealed that he was, at first, unaware of the heated debate surrounding the film. He mentioned then discovering that there were two distinct camps among critics: one that loved the film and another that was disappointed by the lack of a clear moral condemnation for lead character Jordan Belfort's actions. Scorsese himself seemed unfazed by the criticism, stating that such moralistic attitudes were "beyond boring." Scorsese went on to describe an infamous advanced screening of ‘Wolf’ in New York City, which led to heated debate over the moral positioning of the film: Apparently, I was told this: there were two camps [in New York], one camp that loved the picture, the other that was furious and said that I didn’t take a moral stand on [‘Wolf Of Wall Street’ protagonist] Jordan Belfort, and one of the critics from the other camps that liked the picture, said, ‘Do you really need Martin Scorsese to tell you that that’s wrong? The moral rot in ‘Wolf’ was clear as day. You didn’t need critics to point it out, or not understand it. Scorsese's had the last laugh since his sprawling crime epic has become one of the most timely movies of the last decade. Its IMDb score is a highly impressive 8.2 based on 1.5 million votes — it’s also listed as the 132nd greatest film of all-time on IMDb. Many critics included it on their best of 2010s lists. It also features the best performance of Leonardo DiCaprio’s career. It is certainly the riskiest performance from the actor who has never been freer or more playful than as Belfort, the former stockbroker, financial criminal, entrepreneur, speaker, and author who scammed his way to millions. ‘Wolf’ is also the film that introduced many young millennials, and Gen Z, to Scorsese. This epic of high debauchery had scenes veering towards pure slapstick comedy. In a way, it’s as fervently comic a satire as, say, Scorsese’s timely 1983 indictment of ego and fame, “The King of Comedy.” The film predicted a divisive country that was about to combust at any second. Scorsese held up a mirror up to America and reminded us that these are the kinds of guys that own, and continue to flourish, the most power. In a way’ “GoodFellas”, “Casino”, and “The Wolf of Wall Street” can be seen as an unofficial trilogy about the criminal class slowly moving into the mainstream. Outrageously entertaining, the film continues to gather up an audience. This past September, it climbed to the top of the Netflix charts and spawned more conversation than it ever has before. It’s very hard to deny that Scorsese’s film keeps striking a chord with movie audiences, and continues to do so, no doubt due to its scathing relevance.- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

I mostly know him because he's ... well... gorgeous White Collar is a pretty good crime show with him in the main role, then of course the Magic Mike movies with him in a supporting role as stripper Ken. He isn't super famous but as he said himself as a openly gay actor it's not always easy for him to get the same offers as "straight" actors like Leo for example. Fans also wanted him and Alexis Bledel desperately in the 50 shades movies but the producers made very clear "a gay actor wouldn't fit the fantasy". It was pretty disturbing. May their homophobic asses rot in hell. https://ew.com/article/2012/08/09/bret-easton-ellis-50-shades-matt-bomer/- Leonardo DiCaprio - (Please Read First Post Prior to Posting)

^done ✔️ Didn't know Matt Bomer has such a strong fanbase. He's amazing in "Fellow Travelers"; if you haven't watch this show I highly recommend He and Jonathan Bailey are gorgeous Speaking of this

Account

Navigation

Search

Configure browser push notifications

Chrome (Android)

- Tap the lock icon next to the address bar.

- Tap Permissions → Notifications.

- Adjust your preference.

Chrome (Desktop)

- Click the padlock icon in the address bar.

- Select Site settings.

- Find Notifications and adjust your preference.

Safari (iOS 16.4+)

- Ensure the site is installed via Add to Home Screen.

- Open Settings App → Notifications.

- Find your app name and adjust your preference.

Safari (macOS)

- Go to Safari → Preferences.

- Click the Websites tab.

- Select Notifications in the sidebar.

- Find this website and adjust your preference.

Edge (Android)

- Tap the lock icon next to the address bar.

- Tap Permissions.

- Find Notifications and adjust your preference.

Edge (Desktop)

- Click the padlock icon in the address bar.

- Click Permissions for this site.

- Find Notifications and adjust your preference.

Firefox (Android)

- Go to Settings → Site permissions.

- Tap Notifications.

- Find this site in the list and adjust your preference.

Firefox (Desktop)

- Open Firefox Settings.

- Search for Notifications.

- Find this site in the list and adjust your preference.